Turn Every Page: Rhetoric and President Trump

How the tools of rhetoric will likely lead to a Trump win in the Supreme Court

“The rhetorician’s business is not to instruct a law court or a public meeting

in matters of right and wrong, but only to make them believe.

- Plato, Gorgias, 455b

Last week brought with it a great lesson in rhetoric. Most people do not listen to Supreme Court arguments. Most lawyers don’t even listen to the arguments. But last week’s argument in President Trump’s case against the State of Colorado was a masterclass in rhetoric—both the good and the bad.

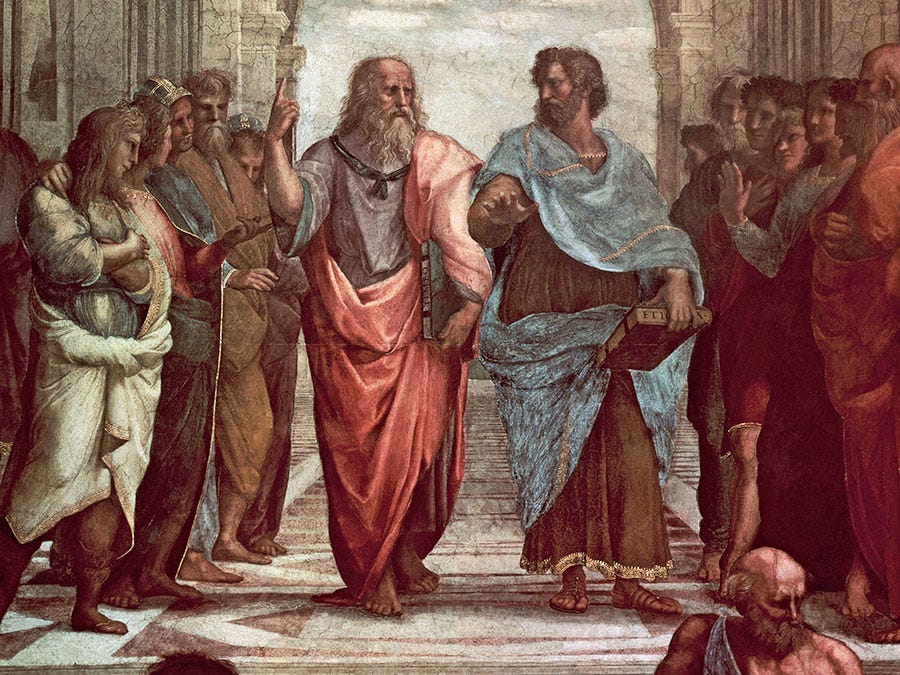

Rhetoric, as Aristotle explained it, refers to a speaker’s ability to discern the means that will be most persuasive to a listener and apply it well. (Rhet. I.1, 1355b10-14). It is a universal art in the sense that rhetoric can be applied to a myriad of subjects—you can use rhetoric to persuade your child just as much as you can use it to get a deal on a used car. But knowing what may persuade another person does not mean that rhetoric will always work. Rather, “its function is not simply to succeed in persuading, but rather to discover the means of coming as near such success as the circumstances of each particular case allow.” In that way, Aristotle explains, it is similar to medicine: “it is not the function of medicine simply to make a man quite healthy, but to put him as far as may be on the road to health; it is possible to give excellent treatment even to those who can never enjoy sound health.” Some patients will never improve; some people will never be persuaded.

Aristotle’s Rhetoric is not a handbook for how to make an argument, but a description of the three tools of persuasion: (1) the character of the speaker (ethos), (2) the emotional state of the listener (pathos), or (3) the reasoning of the argument itself (logos). These three tools are interdependent. You cannot be persuasive relying on only one. It’s a very rare case where someone is persuaded by the force of a logic alone, for example. A persuasive speaker certainly has to have a good argument, but it is an argument that is presented with some personal authority (i.e., a showing of understanding or expertise) and an appreciation of the listener’s situation.

Ronald Reagan was a master rhetorician. During his October 28, 1980 debate with President Carter, he looked at the camera and asked voters: “Are you better off today than you were four years ago?” He didn’t leave it at that. He explained how that question applied to domestic and international issues, national security issues, and national pride. And he made it personal for voters—speaking about rising costs of household goods and unemployment. His argument was simple, and he presented a clear binary choice. The rhetorical power of Reagan’s statement was in how he tapped into the feelings of the listener. It’s no surprise that Reagan was effective given his background in acting. Touching on an audience’s pathos can be as much about what you say as it is about how you say it. And like any good actor or comedian knows, delivery is important.[1]

Sometimes speakers do not use their gifts in a positive way. In Plato’s time, it was the Sophists, those “highly paid and popularly applauded experts in the art of twisting words, who were able to sweet-talk something bad into something good and turn white into black.” Josef Pieper, Abuse of Language, Abuse of Power, 7 (Ignatius Press 1988). The Sophists manipulated words to their own ends regardless of whether they corresponded with reality. When words become corrupted, Pieper argues, “instead of genuine communication, there will exist something for which domination is too benign a term; more appropriately we should speak of tyranny, of despotism.” Pieper, 30. And the manipulation of words “creates on its part, the more it prevails, an atmosphere of epidemic proneness and vulnerability to the reign of the tyrant.” Pieper, 31. Then, when the words are used by those in power, “[s]erving the tyranny, the corruption and abuse of language becomes better known as propaganda.” Pieper, 31.

Words are powerful. But it seems like speakers use words less and less today. What I mean is that most politicians or others seeking to persuade resort to ad hominem attacks, to bluster, and to shouting down critics. They no longer present compelling arguments. Most of the examples of superb rhetoric are ancient ones. Long gone are the days of powerful rhetoric in politics, such as was commonplace several generations ago:

In the presidential campaign of 1900 McKinley was opposed by William Jennings Bryan, whom he had already defeated in 1896. Bryan was no demagogue but a genuine lover of the people, a good man, an honest man, a natural defender of human rights. He had a shallow and opinionated mind, but he also had a magical gift of speech. In those days when there was no radio and no television and when oratory was a widely appreciated art, there was no one who could hold and sway an audience as Bryan could. There are men still living who recall how they came to some county-seat meeting to hear him speak, and how they stirred restlessly on the hard benches during the preliminary addresses; how when Bryan began they listened with skepticism; and how the organ tones of his glorious great voice and the rise and fall of his rhetorical cadences so captured them that when, at last, he came to the end of his peroration, they found themselves hardly able to move their cramped muscles: for two hours they had sat motionless under the spell of his silver tongue.

Frederick Lewis Allen, The Big Change: America Transforms Itself 1900-1950, 85. No one would sit still for two hours to hear a politician speak today. (It’s doubtful one could speak compellingly for two hours.) We have lost that art in politics, whether it’s the two-hour version or Reagan’s pithy question.

Today it is difficult to find great examples of rhetoric outside of politics as well. But last week, we had an example that seems useful to pause and study. Jonathan Mitchell, Jason Murray, and Shannon Stevenson were the three attorneys who argued for and against President Trump in last week’s Supreme Court case, Trump v. Anderson.

Stevenson gave a solid performance as Colorado’s newish Solicitor General. I actually interviewed with her the week after I took the Colorado Bar when she was in private practice. I remember her being easy to converse with and that she gave honest, straightforward answers. She argued very much like she converses—she got to the point, responded to the question asked, and stated her position well.

My interest—and the stark contrast in terms of rhetoric—is in the arguments from Jonathan Mitchell and Jason Murray. Whether you like President Trump or not, Mitchell clearly gave the better performance. He gave what Politico called an “un-Trumpy performance” without the “bombast” that Trump lawyers, and Trump himself, often use.

Mitchell started, interestingly, the same way that Chief Judge John Roberts usually started when he was an attorney. Compare Mitchell’s opening with Roberts’s own opening in United States v. Kokinda, for example. Both of them provide a brief synopsis of the facts, clearly state that they think the decision below was wrong, and then go on to explain specific reasons why. It’s an appeal to logos. They explain their argument and present the underlying premises they will refer back to later in their argument and in response to inevitable questions. When he was a practicing attorney, Roberts was arguably the best Supreme Court advocate in the country. And he was so effective because he relied on these ancient principles of persuasion.

Murray also started by explaining his position, but the divergence in rhetorical power really came in Murray’s failure to use pathos effectively. When a judge asks you a question, you answer the question. It’s a tremendous opportunity for an advocate—you get to respond to exactly what the decision-maker finds interesting, difficult, or dispositive. The same is true of a conversation with a friend or a spouse. If your spouse asks you a question and you never answer it, or try to change the question to suit you better, it does not end well.

Which is exactly what Murray did:

Chief Justice Roberts: “I think you are avoiding the question.”

Justice Alito: “Yeah, but you’re really not answering my question. It’s not helpful if you don’t do that.”

Justice Gorsuch: “I think Justice Alito is asking a very different question, a more pointed one and more difficult one for you, I understand, but I think it deserves an answer.”

Failing to answer a question is a failure of pathos. Pathos is about what the listener wants. Instead of asking yourself what you think the most persuasive thing is, ask yourself what the listener is interested in. In court, the judge specifically tells you what he’s interested in with his question, but this applies elsewhere also. At work: When you ask for a raise, what would persuade your boss beyond the numbers? What can your boss get out of it? Does he want to look good to his peers? Does he want to have some responsibilities taken off his plate and put onto yours? Or with situations at home: Would your kids be more willing to do their chores if there was some kind of reward at the end? Would they become willing participants in cleaning the house if they saw you start to clean as well? What are they feeling that might prompt them to take some action?

The most damning exchange for Murray came from his interaction with Justice Gorsuch. That’s particularly interesting because Murray had clerked for Justice Gorsuch while Gorsuch was a judge on the 10th Circuit. I interviewed with Justice Gorsuch as well, and he was as nice a man as you will meet. He was also very honest (i.e., blunt) and intellectually rigorous. I can only imagine the sparring that went on with his clerks about draft opinions and issues that arose in cases. To me, Murray and Gorsuch were having one of their in camera exchanges like the old days.

But Murray is no longer a clerk, and Gorsuch is no longer his boss. Murray’s job was to advocate for his position, and by failing to answer the question repeatedly—after the justices called him out on it—was a failure in the basics of rhetoric.

Justice Gorsuch grew tired of Murray’s failure to answer the questions: “What would compel – and I’m not going to say it again, so just try and answer the question. If you don’t have an answer, fair enough, we’ll move on.” The three-minute exchange is here.

It made Jonathan Mitchell’s argument look even stronger because, at least, he had straight answers for questions.

Sometimes Mitchell’s answers did not favor his own side, which brings me to what I think was the key to his presentation. Mitchell was deferential and not afraid to call out the difficulties in his own argument. Some of the precedents did not favor his side, or did not favor them as much as he would like. There are practical concerns about how things would play out in the future as states implement some of these things. The January 6 events were, in Mitchell’s words, “shameful, criminal, violent, all of those things, but it did not qualify as insurrection as that term is used in Section 3.” (Argument Transcript)

Mitchell conceded what he could, which gave him additional ethos—professional credibility with the Court. According to Aristotle, ethos includes (1) practical intelligence (prudence), (2) virtuous character, and (3) good will. A really effective speaker has all three. Mitchell gave a great example of (1) and (3). If the justices were expecting to hear an advocate banging on the podium arguing vigorously for his position, they were disappointed. Mitchell argued clearly, answered questions directly, and conceded points where necessary. He sounded more in control of the history and the law than did Murray, which made Mitchell seem like the more trustworthy source of information.

The tools of rhetoric can be powerful means to get what we want, if wielded properly. Used poorly, however, they can have the opposite effect. Time will tell whether the Supreme Court was persuaded given Mitchell and Murray’s different performances.

Remember to turn every page. Enjoy your weekend. Please let me know whether you need anything.

Best,

Aaron

[1] It reminds me of a joke I heard as a kid: A man goes to prison and while he is lying in bed his first night, he hears someone yell, “44!” Everyone in the cell block started laughing. Another person several cells down yelled, “72!” Again, everyone laughed. He asked his cell mate what was going on. His cell mate explained, “We’ve all been in here so long, and we’ve heard everyone’s jokes so much that we just gave each one a number to make it easier.” “Oh,” the man replied, “can I try it?” “Sure, go ahead.” So, the man yelled out, “61!” Crickets. No one laughed and there were a couple of groans on the cell block. “What happened?” the man said. His cell mate shrugged his shoulders and replied, “Some guys just can’t tell a joke.”