Turn Every Page: What to read in 2025

Choosing what to read at the start of a new year, and a challenge.

At the end of 2024, I was inundated by many “best books of 2024” lists from multiple sources. Newspapers, magazines, pundits, schools, and other groups felt the need to recommend books to others, and felt qualified somehow to do so. I so far have 397 books on my recommended book list and I have not yet captured all of what was recommended.

And those are just the nonfiction recommendations. If you add fiction, that probably triples the size of the list.

Wading through those lists can create a bit of decision paralysis. And because of that, we often default to things or authors that already conform with our world view or set of beliefs. Conservatives read conservative authors, liberals read liberal authors. People who support x, y, or z read authors who support those issues or causes. When we are looking online for content, social media algorithms actually reinforce these tendencies, multiplying this “echo chamber” effect we experience by only reading things that reinforce our beliefs. As a result, we are fed more of the same kind of content we just accessed and we are rarely offered new ideas or perspectives.

In his book, Them, Senator Ben Sasse discusses this social-media trend and how one of the byproducts is that it isolates people from one another. Worse than creating mere isolation, social media (and media in general) promotes the most extreme sides of a viewpoint. This is not a new phenomenon, but social media has certainly made it worse.

Being a litigator helps, I think, to understand that there are at least two sides to every issue. An effective advocate could argue the opposite side of the case just as effectively as his own. (In fact, that’s a common requirement for speech and debate competitions.) But a lot of people never take the time to see that there is another side, much less to actually understand it. That’s a dangerous position to be in intellectually speaking. If we never talk to people or engage with ideas that are different from our own, we start to look absurd. Sasse recounts

New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael’s (in)famous remark that she had no idea how Richard Nixon had won the presidency: ‘I don’t know anyone who voted for him!’ Nixon in 1972 carried every state except Massachusetts, and tied for the largest popular vote in U.S. history (61%), and yet in many liberal neighborhoods in Eastern cities, his victory was utterly inexplicable. (Them, at 88)

This is not a liberal-conservative issue. The issue is that someone like Kael, who was probably regarded as a well-educated person, had cut herself off—deliberately or otherwise—from the prevailing sentiments of the country. It’s inconceivable that someone who was paying attention would miss that Nixon was popular enough to win the way he did. But Kael had created her own echo chamber of like-minded friends and family that actually skewed the information she received and believed.

Artificially choosing your information solely to fit the beliefs you already have is a form of confirmation bias. It is perfectly natural to look for things that support your own viewpoint. And we enjoy reading things that affirm our beliefs. It is uncomfortable to be challenged in your views or to confront new ideas. Recognizing the role confirmation bias plays in forming our beliefs and in our reading habits “should nudge us toward more humility about even those things we think of as unquestionably true.” (Them, at 86)

What would happen if people deliberately read things that were written by people with a different perspective? What if they did that even 25% of the time? I have done this for years out of habit. There are many writers I read, knowing that I will disagree with their arguments or conclusions. But I read them because they are the best proponents of their particular views. Reading something by a careful and thoughtful writer on any side of an issue makes you think about that issue more deeply, but particularly when presented from an opposite or different perspective.

Reading opposing viewpoints may not convince you to change your mind. And that is not necessarily the point. Rather, you come away from reading different viewpoints with a better understanding of your own. You can better articulate your point of view. You can argue for your own position better because you now understand an opposing perspective.

It also helps you wrestle with ideas rather than the people espousing them. If you read broadly, it seems that you are less prone to the yelling and ad hominem attacks so common in the mainstream media. As I noted in my last essay, many people criticized Donald Trump for using the phrase “Make America Great Again” without realizing that it had been used to great effect by Bill Clinton before him, and Ronald Reagan before him. People criticized Trump’s use of the phrase because it was Donald Trump using it, not because the phrase or concept was a bad one. They were anti-Trump, so they were anti-anything-Trump-says.

This kind of reaction is a by-product of what Sasse talks about when he describes how we are losing a sense of shared community and becoming a series of “anti-tribes”: people are anti-this or anti-that rather than taking a positive and constructive position in favor of something. The focus on the negative side of things (“I’m not pro-Harris, I’m anti-Trump”; “I’m not pro-Red Sox, I’m anti-Yankee”) is a form of anti-intellectualism that has become commonplace. We have replaced the hard work of learning facts, understanding an issue, and arguing reasonably for our point of view in favor of listening to talking heads on the television whose stock-in-trade is yelling, blaming, and name calling.

So what does that have to do with what you read in 2025? My proposal, and challenge, to you is that we recover part of what “Turn Every Page” refers to. One aspect is to turn every page in the sense that we do not leave anything uncovered, that we read each page of a book or article, like Robert Caro’s rules for research. But the other aspect is that we turn every page—we do not shy away from reading certain things because they are difficult, they do not fit our belief system, etc. We read widely to gain knowledge and come to a deeper understanding of the truth. One way of doing that is by reading different perspectives and positions that are sometimes contrary to ours. Or, as Cal Newport recommends, read good thinkers on both sides of an issue to gain understanding when you are not familiar with a particular topic or event.

If you are new to reading seriously or have decision paralysis, it is easy to turn to a “best of” book list and start from there. But think: who picks what goes on the list?

In any list, there will be a kind of confirmation bias that goes into picking certain works over others. In fact, some lists actually seek to rank one “best book” over another, resulting in some questionable conclusions. For example, the website thegreatestbooks.org seeks to aggregate rankings from a variety of lists. Its “list represents a comprehensive and trusted collection of the greatest books. Developed through a specialized algorithm, it brings together 459 ‘best of’ book lists to form a definitive guide to the world’s most acclaimed books.”

A “definitive guide”? I think not. The Greatest Books ranking lists Frederick Douglass’s Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass as the 789th best book of all time, even though it cites other lists that put the book in the top 100 or even the top 10 of all time. If this were purely an objective analysis, the lists would be the same, or at least very similar. They would not judge the same book hundreds of places apart if they were considering the same criteria. But someone had to create the algorithm, which inevitably favors x over y, and emphasizes what the algorithm creator thought was important.

If you were just choosing books based on popularity over time based on sales, you would read the Bible, all of Shakespeare, and Agatha Christie. You’d benefit from reading all three, but volume of sales is not necessarily the go-to criterion. (Plus, you’d be reading a lot of James Patterson and his many co-authors, which is not a great idea.)

So if the rankings cannot fully be trusted, and you don’t choose based on popularity, how do we choose a book? Many of the things I read are recommendations from someone I know and trust, or from a public intellectual who has some authority in the area. Maybe that is not the best way to pick books, but it’s what I do.

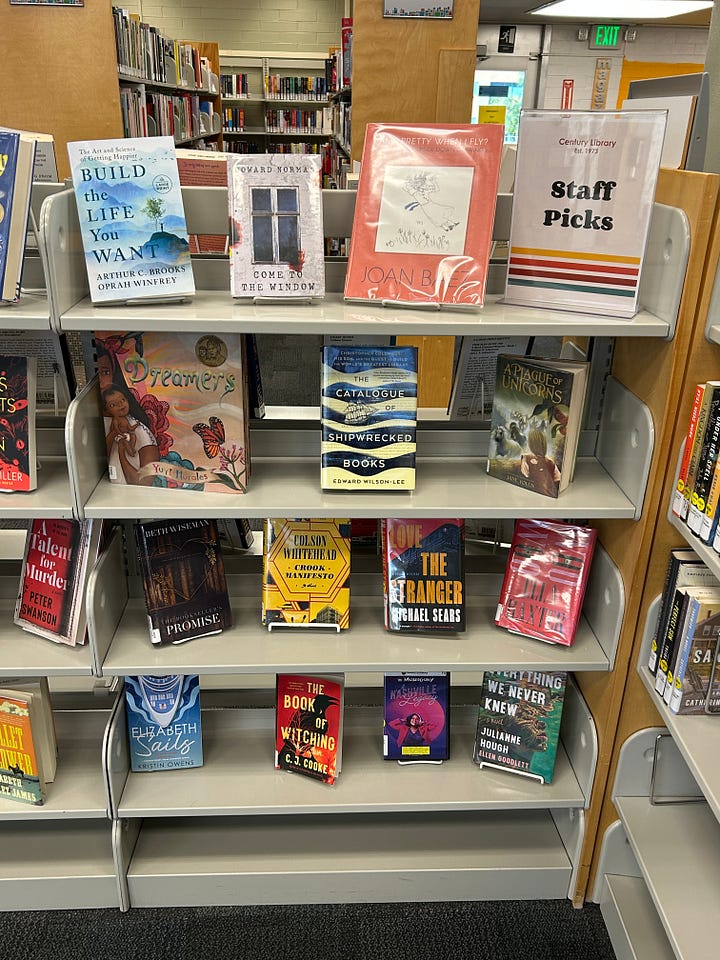

You could see what people in your community are reading. That would present an interesting mix of topics and genres. If I did that, I might read all the books below—recommendations from my local library and the two closest Little Free Library locations (there are 29 within about a two-mile radius of my house).

That seems kind of random, though. Although I see the librarians a lot, I don’t know them, so I don’t necessarily trust their recommendations. And Little Free Libraries have an ever-changing and unpredictable stock of books. I think it’s better to be intentional about what you read.

Many people recommend reading “The Western Canon,” a list of books that has been a cultural touchstone of the last several millennia. These are classic works that have been the foundation of civil society for many cultures through many ages. And no doubt, we would benefit from reading them all. We’d probably become more human and humane. We’d grow in understanding of ourselves and the world. In a way, the Western Canon is the classic “best books of all time” list.

But a lot of people think the Western Canon is outdated or not relevant today. Marc Andreessen, the uber-successful investor, explained his method for choosing books on the How I Write podcast. He balances the need for new things and classic texts by taking a “barbell” approach, reading only what is either “super-current” or “timeless.”

That makes sense for someone who is focused on evaluating cutting-edge business ideas to see whether he wants to invest, while also remaining grounded in ideas that have stood the test of time. Maybe you read a new release followed by a classic Greek or Roman author throughout the year. But Marc Andreessen’s approach doesn’t work for everyone.

Here is an approach that could work for everyone. It requires a bit of thinking, and you might not like everything you read:

What if we all chose books in 2025 that are more likely to make us more human and humane by the end? Sasse quotes C. John Sommerville from his book, How the News Makes Us Dumb: The Death of Wisdom in an Information Society. Sommerville argues that we can benefit far more from books than the constant stream of 24/7 news: “If news were just one of many things that we read each day, it wouldn’t have the same impact. If we would read science, the classics, history, theology or political theory at any length, we would make much better sense of today’s events.” (Them, at 79)

Ask any author or influencer how they choose what to read and each will likely give you a different answer. But here’s the key—they will always have an answer. They are always reading. President Harry Truman’s quote is true: “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.”

The Western Canon may have become less influential over time, despite the growth and success of many classically oriented schools. At a certain time in history, having familiarity with the Canon was what designated someone as being educated. Today, those standards have changed, and they will continue to shift. Yet, reading anything changes how we think and, as a result, often changes who we become. You probably know that Bill Gates famously took at least two weeks a year as “think weeks” when he ran Microsoft. Those weeks were some of the most fruitful weeks of his year, and they were all focused on reading, sometimes 18 hours a day. We likely do not have the luxury to take weeks out of our year to devote to reading, but we can carve out time each day to read. Try dropping social media. Try not reading or watching the news. That alone would free up several minutes—if not hours—of time to read and think and explore more substantive ideas. Taking time away to read and think has been a central practice of many leaders through time. (See Judge Kethledge’s book on the topic.)

Even if you are not a “leader” in an official sense of the word, you still need to lead yourself, as Judge Kethledge suggests. And reading, I argue, is a key to grappling with ideas, understanding those ideas, figuring out your position on those ideas, and implementing them in your life. It’s important work.

If reading is difficult for or foreign to you, here is some practical advice. In her January 2 New York Times article, “Giving Kids Some Autonomy Has Surprising Results,” Jenny Anderson makes several observations that could help guide our own approach to reading. She was surveying tactics that educators and parents use to engage their children more, but we can use these same tactics on ourselves.

At the start of a lesson, instead of providing a step-by-step schedule and overview for the class period, as many good teachers do, they inquired about the kids’ own interest. They might say, “Today I’m going to tell you about the solar system. Before we start, is there anything about the solar system that you are particularly curious about or have a question about?” This simple step encourages kids to think about what they know, what they care about and what they want to know more about, rather than just settling in and tuning out.

We can easily do the same thing with ourselves. You may pick up a book and say to yourself, “Here is a book about the history of Arab-Israeli conflict. What do I think I know about this topic? What questions do I have that I want answered by reading this?” Even if the book’s topic does not immediately command your attention, and even if the author has a different perspective than your current understanding of a topic, you can read the book fruitfully by going into it with an open and inquisitive mind.

Books have that power. As Anderson suggests: “Maybe it’s time to define a higher ideal for education, less about ranking and sorting students on narrow measures of achievement and more about helping young people figure out how to unlock their potential and how to operate in the world.” For those of us long past the student stage, we can still “unlock [our] potential and [learn] how to operate in the world” by reading books.

So whatever “best of” list you find, or recommendation you receive, I think the key is to receive it with an open mind. We have libraries, and they are a no-cost way to explore ideas. And if you read something from the library and dislike it, you didn’t waste any money on it. But if you liked something, you are all the better for it. Just keep reading.

Remember to turn every page. Enjoy your weekend—and the start to 2025. Please let me know whether you need anything.

Best,

Aaron