Vivek Ramaswamy recently had a long post on X about H-1B visas and American culture as it relates to immigrants and the contributions that immigrants have made. Ramaswamy argues that “[t]he reason top tech companies often hire foreign-born & first-generation engineers over ‘native’ Americans isn’t because of an innate American IQ deficit (a lazy & wrong explanation). A key part of it comes down to the c-word: culture.” He goes on to explain that “American culture has venerated mediocrity over excellence for way too long.” But for Ramaswamy, “excellence” seems to be associated solely with academic or intellectual achievement at the expense of other types of excellence. While I share his “More books, less TV” sentiment, excellence can be found outside of the classroom as well. There is great value, for instance, in athletic pursuits that instill the virtues of discipline and hard work in young men and women. Those traits often make people more successful in life than those who have only book smarts and no drive to go and produce something. Piling up academic credentials does not—in itself—make someone “excellent.” It might just make them pedantic and snobbish.

In general, though, I appreciate Ramaswamy’s desire to see “[a] culture that once again prioritizes achievement over normalcy; excellence over mediocrity; nerdiness over conformity; hard work over laziness.” Immigrants are certainly known for their industriousness and entrepreneurial spirit. And Ramaswamy’s comments remind me of the virtues extolled by early Americans like Jefferson, Hamilton, and Franklin and the idea of the “self-made man.” Franklin was the prototype of the “self-made man.” He had that reputation while he was alive, and his grandson William Franklin helped perpetuate the reputation later.

But it was all false. Around the time I saw Ramaswamy’s comments, I also stumbled upon John Swansburg’s article in Slate: “The Self-Made Man: The story of America’s most pliable, pernicious, irrepressible myth.” The stories we often tell about rags-to-riches triumphs are romantic, but often not true—or at least not the full story.

I guess I was afraid that there was this version we all kind of know because it’s out there in the ether, and the idea is you can be born poor in America and if you work hard enough, this is the land of opportunity, and people who want it badly enough and are willing to put in the sweat will get what they want. I think we can all recognize that that’s an ideal, it’s certainly not true for everybody, and I talk about the distance between the mythology and the reality in the piece, but I guess I was afraid on those first days that that was just the idea and Franklin inaugurated the idea and here we are today and we still believe it, kind of weirdly because it doesn’t happen that often, and yet we still buy into it.

The reality is, as Aristotle stated long ago, that we are social beings. If we are left alone, we are “not self-sufficing.” We need others to become who we are, particularly when it comes to growing in virtue, in tempering the sharp edges of our personalities, and creating a civil society.

The proof that the state is a creation of nature and prior to the individual is that the individual, when isolated, is not self-sufficing; and therefore he is like a part in relation to the whole. But he who is unable to live in society, or who has no need because he is sufficient for himself, must be either a beast or a god: he is no part of a state. A social instinct is implanted in all men by nature, and yet he who first founded the state was the greatest of benefactors. For man, when perfected, is the best of animals, but, when separated from law and justice, he is the worst of all; since armed injustice is the more dangerous, and he is equipped at birth with arms, meant to be used by intelligence and virtue, which he may use for the worst ends. Wherefore, if he have not virtue, he is the most unholy and the most savage of animals, and the most full of lust and gluttony. But justice is the bond of men in states, for the administration of justice, which is the determination of what is just, is the principle of order in political society.

(Aristotle, Politics, Book I, part 2). Justice and civil society come about because we gather into human communities—first a family, then a community, a city, and then a state. It is in those communities that we learn about virtue and where we can apply the principle of justice.

There’s a different way to think about this described in the movie “Good Will Hunting.” When Sean the therapist (Robin Williams) asks Will (Matt Damon) at one point whether he has a soulmate, Will lists a number of great thinkers: “Shakespeare, Nietzsche, Frost, O'Connor, Chaucer, Pope, Kant.” Sean quickly points out that they are all dead and Will can’t be in an actual relationship or dialogue with them. A later monologue captures something similar:

In the discussion, Sean describes how human connection—with live human beings—is a key to growth. We need others to help us, challenge us, and allow us to become who we are. For Will, that required him to be vulnerable.

Maybe that is why immigrants can thrive when they are supported by communities around them. Think about the image of immigrants just “off the boat” in New York or some other city, setting up a business, and pursuing the American dream. They are among the most vulnerable people you could think of—they are in a new culture with a new language in a new kind of economy and needing new connections to succeed. The immigrants who do succeed do so largely because they came here with others, or joined a community of family or others from the same country who already came to the United States. They work hard and put in the effort, but the community is essential to their success.

Many of the stories we hear about immigrants have a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps theme to them, and we marvel at people’s success as first- or second-generation Americans. But as Swansburg notes in his article, the self-made man is a self-made myth. Many people we label as self-made throughout time or nothing of the sort. When Hillary Clinton claimed that it takes a village to raise a child, she may have been wrong about children, but she did point to a deeper truth about humans and how we become thriving businessman, scholars, or just plain human beings.

Take the example of Abraham Lincoln. In Team of Rivals, Doris Kearns Goodwin explains how Lincoln brought his closest political rivals—those he fought in the Republican primary before his election—into his administration and made them his closest collaborators. They did not all buy into the plan. Salmon Chase, the governor of Ohio, did not agree with Lincoln and even after being appointed to his cabinet, sought to undermine his administration to become the Republican candidate in 1864. Lincoln’s reaction to dissent was not to dismiss everyone and go it alone. In fact, he did not even remove Chase. Rather, Lincoln kept Chase in the cabinet and eventually appoint him as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1864.

Goodwin argues that it was Lincoln’s ability to build relationships and a coalition that was the secret to his political success. I think it’s a compelling argument. But Lincoln’s genius goes beyond political success. Lincoln was willing to be vulnerable enough to welcome different viewpoints into his administration, and it made him a better person in addition to being a better politician.

Maybe you have had a similar experience. In college and grad school, I was in a supportive community of thinkers and future scholars. It was a place where people worked hard at their studies, but did so within the context of a community. We thoughtfully challenged others not to win a point, but to clarify an argument and to make each others’ thinking better.

Thinkers do not become great thinkers when they are sitting comfortably in an ivory tower. A good example of this is the oft-cited example of Bell Labs. Mervin Kelly, the Chairman of the Board for Bell Labs, deliberately designed his company’s headquarters to favor human interaction and support. There were no self-made men or ideas at Bell Labs.

[Kelly’s] fundamental belief was that an “institute of creative technology” like his own needed a “critical mass” of talented people to foster a busy exchange of ideas. But innovation required much more than that. Mr. Kelly was convinced that physical proximity was everything; phone calls alone wouldn’t do. Quite intentionally, Bell Labs housed thinkers and doers under one roof. Purposefully mixed together on the transistor project were physicists, metallurgists and electrical engineers; side by side were specialists in theory, experimentation and manufacturing. Like an able concert hall conductor, he sought a harmony, and sometimes a tension, between scientific disciplines; between researchers and developers; and between soloists and groups.

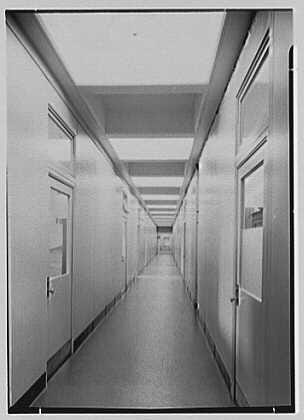

One element of his approach was architectural. He personally helped design a building in Murray Hill, N.J., opened in 1941, where everyone would interact with one another. Some of the hallways in the building were designed to be so long that to look down their length was to see the end disappear at a vanishing point. Traveling the hall’s length without encountering a number of acquaintances, problems, diversions and ideas was almost impossible. A physicist on his way to lunch in the cafeteria was like a magnet rolling past iron filings.

Kelly’s deliberate design of the office makes a lot of sense if you are trying to build in the ebb and flow of tension and harmony that can lead to great ideas. The fundamental belief that Bell Labs would make better things and come up with better ideas when people were collaborating is something we should think about. I love remote work and appreciate the flexibility it affords people, but there is a different experience when you have colleagues down the hall. It is something to think about when many have a no-presence-in-the-office-after-Covid mentality.

While Kelly’s architecture was deliberate, some people are thrust into a community by circumstances. That’s one way to set the stage for the story told in Metaphysical Animals: How Four Women Brought Philosophy Back to Life. Elizabeth Anscombe, Mary Midgley, Philippa Foot, and Iris Murdoch (the ladies pictured at the top) all came to Oxford at the same time right before many men at Oxford were heading off to fight in the Second World War. After the men “were uprooted from Oxford and replanted in Whitehall and the War Office,” “philosophy began to come back to life.” (xi) Philosophy moved from an effort “to kill off the subject formerly known as ‘philosophy’ and to replace it with a new set of logical, analytic and scientific methods known as logical positivism” (x) and returned to a philosophy that was “free once again to speak of poetry, transcendence, wisdom and truth.” (xi)

These four women changed the trajectory of philosophical inquiry at the time. “The ‘hero’ of modern philosophy is, Iris wrote, the ‘offspring of the age of science’. He is ‘free, independent, lonely, powerful, rational, responsible, brave, the hero of so many novels and books of moral philosophy’. But he is alienated from his own nature, from the natural world that is his home and from other humans.” (xii-xiii) He sounds, in short, like the “beast” who is not able to live in society that Aristotle describes. Philosophy had taken as an ideal the self-made, individualistic man.

Philosophy recovered, in part, because the people recovering it were women. Midgley “argued that the solipsism, scepticism and individualism that is characteristic of the Western philosophical tradition would not feature in a philosophy written by people who had shared intimate friendships with spouses and lovers, been pregnant, raised children, and enjoyed rich and full and varied human lives.” (ix) But in addition to being women, these women were so influential in recovering philosophy because they did it as a group: “the life of humans must, for humans, be studied from within. And if the task is to discover what we are, then it is one that we must attempt in company, as these women did; in college rooms and dining halls, tea shops and living rooms, by post and in pubs, among nappies and babies.” (xiii) The community these four developed was what gave life to their work. They could encourage each other, challenge each other, refine each other’s ideas, and recover what it meant to be human even in a time of war.

These women were forces in their own rights. When Anscombe was looking for a position in October 1957, Philippa Foot wrote that Anscombe “is ‘probably the best all round philosopher (although not the best logician) in the University, at the present time.”1 (7) Foot “was the granddaughter of US President Grover Cleveland” and had a privileged upbringing. (60) Mary and Iris had upbringings more similar to Anscombe and they met her “during that first term of Greats, Trinity 1940.” (72) Then, “Philippa and Mary also became friends that term.” (72)

The friendships they developed directly influenced their thinking. The kind of metaphysics these women promoted made sense because it came out of a deeply connected community. Midgley said that the story of these women was “the story of herself and her friends [that] was to begin with them knitting together the great cleavage in reality” brought about by the previous generation of philosophers at Oxford. (187) “On the knitting needles would go Philippa’s notes on Aquinas (one of ‘the best sources that we have for moral philosophy’); fragments of Wittgenstein’s latest writings turned out of Elizabeth’s pockets (forms of human life); Mary’s inky notes on Plotinus (reality not existence); Iris’s heavily annotated copies of Gabriel Marcel’s Être et avoir (problems and mysteries).” (187)

Ultimately, “what mattered most [to them] was to bring philosophy back to life. Back to the context of the messy, everyday reality of human life lived with others.” (295) And they got to explore the messiness of reality together, in their little community that ended up producing so much more than they could have done individually.

The myth of the self-made man is the myth that we can do everything on our own, that we can truly thrive without others. But the reality is that we become better thinkers, politicians, businessmen, and human beings by being around others in a community. The images of Ben Franklin, Dale Carnegie, Horatio Alger, or the others that Swansburg mentions are attractive because we want to believe the stories. But the stories are empty. As Swansburg notes, “It’s no surprise that Alger’s novels have disappeared from school curriculums and library shelves. There’s more narrative tension in an episode of Scooby-Doo than an Alger novel. Even a grade-schooler is liable to roll his eyes at the earnestness of Alger’s prose, the absurd plot contrivances that move the stories along, and the dumb luck that wins the hero his respectable employment. What is surprising is that the books remained popular for as long as they did.”

I’m sure the stories hung around as long as they did because we want to believe them. We want to believe that hard work is sufficient to go from low circumstances to the heights of whatever we are pursuing. We want to think we could be the next Andrew Carnegie just through hard work. We idealize the end result and gloss over the fact that these people actually had a lot of help—from people or circumstances—to get them where they were. If Bill Gates had not attended a school that was wealthy enough to offer students access to a computer (in 1968 when he was 13), it’s likely that he would not have started Microsoft. Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Donald Trump, and the list goes on—they found a lot of their success because they came of age at the right time in history and because they had a supportive network behind them.

Swansburg realized the power of circumstances with his own father, whom he looked up to as a self-made man who built a roofing company:

So he started this small company, and somewhat by luck, it was a moment where roofing technology was changing, the materials were changing, the asphalt had been what you roofed with before, now it was going to rubber, and that change seems like kind of a banal thing, but it turned out to mean that you could be a very small operation, you could bid on a very big project and underbid some of the bigger players, and you could go in with a small crew of guys and go in and do a job and do it well. And so the circumstances of his success were somewhat created by these extrinsic events, just a change in roofing material. And that was something I had never known, and it complicated his self-made story for me. It wasn’t just he imposed his will on the world, it was that he did that at a moment where it was possible to succeed for these other reasons.

When paired with hard work, luck, circumstances, and community are the more likely explanations for success. Work is necessary, but not sufficient, to reach our goals.

We should build and cherish the community of people we rely on for support. They will help us achieve things we never knew possible—and make it a much more enjoyable experience along the way.

Remember to turn every page. Enjoy your weekend. Please let me know whether you need anything.

Best, Aaron

Anscombe’s personal standards were very high. She explained to Iris when they met that “No second rate philosophy is any good. . . . One must start from scratch—& it takes a very long time to reach scratch.” (188)