A friend of mine and I were talking about his recent fly-fishing excursion in Montana. I went with him last year, but couldn’t make the trip this time. Fly fishing was new to me last year. After three days on the river, I understood what the true believers say about it, perhaps captured best by Norman Maclean in A River Runs Through It: “In our family, there was no clear line between religion and fly fishing. We lived at the junction of great trout rivers in western Montana, and our father was a Presbyterian minister and a fly fisherman who tied his own flies and taught others. He told us about Christ’s disciples being fishermen, and we were left to assume, as my brother and I did, that all first-class fishermen on the Sea of Galilee were fly fishermen and that John, the favorite, was a dry-fly fisherman.”

For someone who has never been fly-fishing, it seems odd to connect—or even equate—religious practice with fly-fishing. But there is definitely a connection: “in a typical week of our childhood Paul and I probably received as many hours of instruction in fly fishing as we did in all other spiritual matters.” It’s not unlike the experience one may have in the vastness of nature while on a hike or other trip. You can connect things that are other-worldly with the world and activity around you.

Toward the end of Maclean’s story, one of the sons is speaking to his preacher father at the edge of the river. His father explained how he had been reading the Gospel of John, which said, “In the beginning was the Word.” They then went on to discuss whether the word was first, whether the water before them was first, and how maybe there was a divine interplay between the two. For them, fishing and religion were indistinct. They were true believers in the redemptive power of both.

We need true believers. In fact, true believers are sometimes the only ones who are able to push things forward, whether in business, family, religion, etc. They are often, in the words of impeccable 1990s Apple marketing (see below), the “crazy ones”—“Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.”

But true believers do not need to be, and are not usually, some David Koresh kind of figure. Believers are not cult leaders. They are visionaries who point other people toward—and often lead them toward—a better or different point of view.

Over the last month, I’ve read several books about a wide variety of topics. Stepping back, however, there is a common thread running through them all, which is the impact that a true believer can have on an organization, a family, or others generally. Take Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon by Michael Lewis. This book analyzes Sam Bankman-Fried, from his early life and entry into the world of crypto trading to the disastrous end of his company. Sam’s downfall was not only tragic for him—he’s serving decades in prison—but for the many people who followed him.

At one point, Alameda Research (Sam’s company) discovered that they had misplaced $4 million. Those working with Sam had “all grown to fear how little he worried about where exactly their money was. They were making two hundred fifty thousand trades a day and their system had somehow lost, or failed to record, some large number of them.” (176)1 These employees worried about very serious and practical things—“How are we going to pass an audit if we’re missing ten percent of our transactions?” How will they file “an honest tax return”?—and “[t]he prospect of losing a couple of hundred million dollars that would have otherwise gone into solving the world’s problems felt pretty high stakes” to most of the employees. Not to Sam.

Before Sam was a believer in crypto and the world of high-frequency trading, he was a true believer of the effective altruism school of thought. Effective altruism is, simply, the belief that you should do the most good for the greatest number of people. Bankman-Fried was introduced to the idea during a lecture given by Will MacAskill, who told high-performing students at Harvard, MIT, and elsewhere that they should pursue a career where they could either directly benefit others or pay for people to directly benefit others. So that could mean becoming a researcher and finding a cure for some disease. But you could be the best researcher and never solve the problem. That is why others believed that the path was to make as much money as possible so that you had the means to fund 10 or 100 world-class researchers who could do the work of finding a cure.

Sam quickly became obsessed with making money. And although he may have had good intentions about what to do with his earnings, the pursuit blinded him from other things. Back to the missing $4 million. While others, “[u]nder the circumstances, . . . thought it was insane to continue trading, . . . Sam insisted on trading. Crypto markets would not remain inefficient for long. They needed to make hay while the sun shone.” (176-77) Sam had found a loophole in the timing of crypto trades across different markets, and the ability to exploit that loophole before others caught on would not last forever. Because he believed that trading crypto was the way to make money, and making money was the way to do good, then he simply could not stop.

Bankman-Fried’s belief in the crypto markets and his need to make money led to his downfall. Others have been tempted by the same forces in an attempt to make money or build a business. A fascinating book, The Fish That Ate The Whale, chronicles the life of Samuel Zamurray, America’s “Banana King.” Zemurray believed that bananas—a once odd and tropical fruit in America—could be big business. So, living in Mobile, Alabama, he got a fruit cart, bought cheap bananas that had started to ripen on the boat, and sold them to merchants near the docks. He then expanded by thinking differently—he lined up customers at rail depots on lines running out of Mobile so that there would be no additional delivery costs beyond the train. People came to the train station to meet him rather than Sam having to add more to his delivery time. He saw a market and an opportunity to deliver ripe or near-ripe bananas quickly.

More importantly, Sam Zemurray believed in himself. He immigrated from Russia with nothing and after saving a couple hundred dollars, he put everything he had into the business. In a short while, Zemurray had more than $100,000 (in the late 1800s) and became a major player in the banana market. In fact, Zemurray parlayed his early success into an interest in United Fruit, the dominant entity in the market.

Zemurray was not satisfied with partnering with the largest player in the market. He wanted to be the largest player. So Zemurray took steps to own or control the means of production, the shipping vessels, and the distribution network. He wanted to own the complete vertically integrated system to squeeze all the money he could from every increase in efficiency.

At the same time, he was also squeezing what he could out of the locals. Zemurray’s belief in his business resulted in him allying himself with rebel groups in Central America, leading to a coup in Honduras and his hiring of mercenaries to carry out a regime change—all for the benefit of his banana business. The new government was more favorable to Zemurray’s company and would give greater concessions in taxes, land acquisition, and other things that would help Zemurray expand his empire.

Eventually, however, Zemurray’s strident belief blinded him to several realities. He was not able to expand indefinitely, and his competitors (as well as banana diseases, foreign governments, the US government, and so on) gained an edge. Like Bankman-Fried, Zemurray had a laser-like focus on his business, but by so doing, he missed the bigger picture. He failed to see the larger context in which his business operated and how slowing down may have benefited his company in the long term.

True believers often have a blind spot, and it is hard for them to shake it. This makes it nearly impossible at times for them to consider another point of view. Think about a mother whose son is on trial for a crime. Sitting in the courtroom, she has a very different perspective than one of the jurors. Even in the face of damning evidence, the mother will remain steadfast in her belief about her son in a way that a juror sitting across the courtroom will not. The mother’s bond with her son and her belief in him clouds her judgment. She cannot hear the evidence the way a juror does, or objectively sift through the facts. Her belief leads to a myopic view.

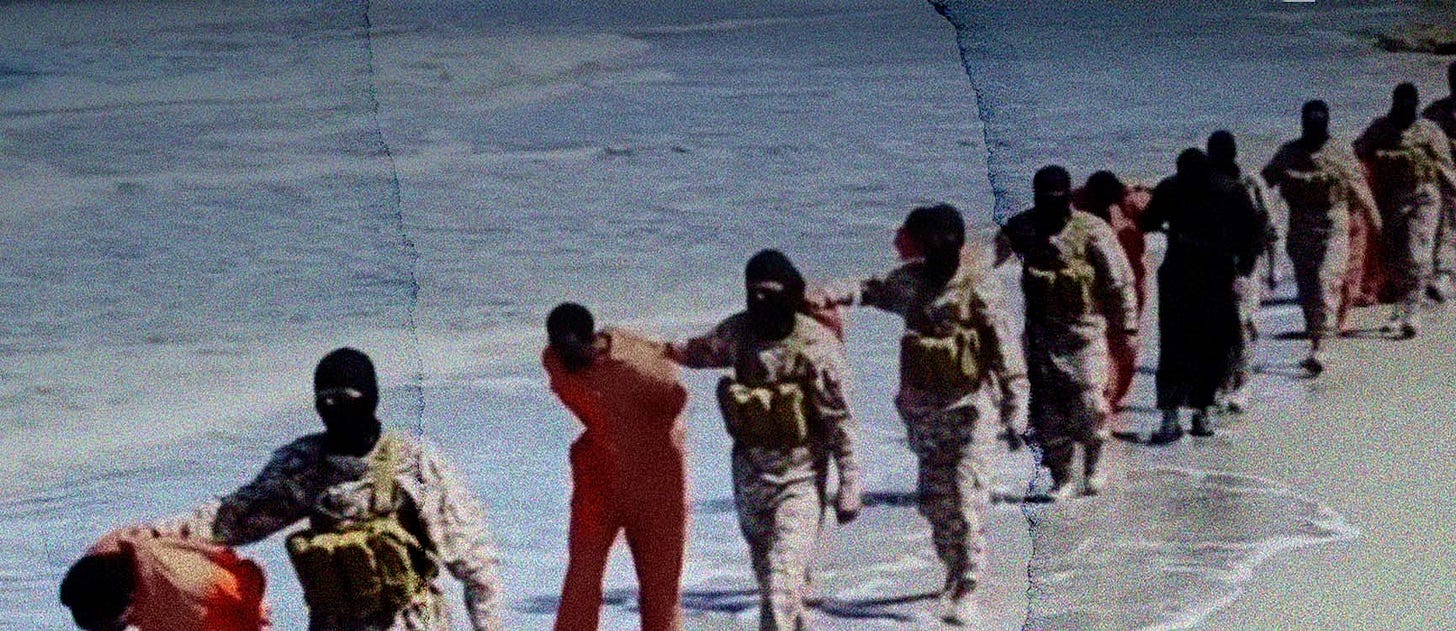

Myopia is not always a bad thing, of course. Sometimes it can be a saving grace. That was certainly true for the 21 Christian martyrs who were killed by ISIS in Libya. In The 21: A Journey Into the Land of Coptic Martyrs, the author details how 20 Egyptian Coptic Christians and an acquaintance from Africa went to work in Libya to provide for their families, only to be captured by ISIS, tortured, and eventually beheaded on the beach in a terrible propaganda video. Through it all, the men stood firm in their faith and kept focused on the source of their belief. For them, a myopic view was a protection. If they saw what was going on around them, or if they thought too much about their loved ones back home, they may have wavered in their belief and run from their martyrdom. They remained focused on the one thing that mattered to them, singing hymns to bolster one another, and forgiving their executioners moments before those same men slit their throats. True believers.

Thinking about the consequences that the 21 Coptic martyrs faced for their beliefs, calling people “true believers” in other contexts seems to lack force. We often think our mundane beliefs are matters of life and death when they are really just preferences. In situations like this, I’m always reminded of the quote attributed to Wallace Sayre: "The politics of the university are so intense because the stakes are so low."

For instance, people think politics have life and death consequences, but—at least in the United States—we generally pass from one administration to another in relative peace. We can be true believers about certain issues, which sometimes concern life and death, but there will always be another election season, usually starting earlier than you think.

Karl Rove’s The Triumph of William McKinley tells the story of the 1896 election and how it still influences American politics today. For McKinley, the issues of the day were focused on the economy. Specifically, the fight was about protectionism and tariffs, as well as the debate between gold and silver supporters. These issues drove the campaign, and McKinley argued for one side of the debate. But McKinley had a gift of being able to turn others into believers. McKinley would give speeches from his front porch to various groups who came to see him. He shaped his message to the group at hand, and could turn financiers and factory workers alike into true believers. The people he talked to may have believed in the gold standard for different reasons, but McKinley had brought them all into the fold, which is likely why he had broad support in areas where Republicans had historically not been successful.

McKinley had a gift of being able to shape his message for a particular listener. Today, the danger of social media and other kind of online interactions is that we risk walking into an echo chamber of our own ideas. Rather than having multiple inputs from multiple sources, we defer to algorithms to tell us what we are interested in. Then we artificially close ourselves off from ideas simply because they do not appear in our newsfeed. McKinley, by contrast, engaged in a real dialogue with people to convert them to his way of thinking. It’s hard to have a real dialogue with people using today’s media.

Seventy-five years ago, the new media was television and that was a means for true believers to spread their messages. In Oral Roberts and the Rise of the Prosperity Gospel, the author gives us a glimpse into the man, Oral Roberts, and his rise to become one of the foremost television evangelists of his day. Growing up poor, his family settled in Oklahoma, where a new denomination of Christians was growing rapidly.

Pentecostalism derives its name and teaching from the feast where the Holy Spirit was poured out upon the faithful. In its modern instantiation, Pentecostalism began when Charles Fox Parham, a former Methodist minister, witnessed people at his church speaking in tongues. He took that as a sign—“the ‘initial evidence’ of the baptism of the Holy Spirit.” (11) Parham went to preach this teaching throughout the midwest and south, and then around the country, gathering people for revivals that drew a wide range of people.

Oral Roberts was introduced to Pentecostalism through the revivals, but also through another one of its main tenets, prayer for and healing of the sick. Roberts had contracted tuberculosis in his teens and was dying. The doctors who saw him were at a loss, prescribing everything from residence in a sanitorium, where Roberts would have access to the potentially healing open air, to “a strict diet of raw eggs beaten in sweet milk.” (19) Roberts always believed in the power of modern medicine, but everything that the doctors tried had failed.

“With the doctors unable to cure Oral and death knocking at the door, prayer was the only thing left to try.” (20) His older sister had told him, “Oral, God is going to heal you.” (20) And, in time, Roberts came to that belief as well. At a revival, in July 1935 when he was 17 years old, Roberts was cured of his TB.

By August 1935, Roberts had decided to enter the ministry. His physical healing had made him a true believer, and he dedicated his life to trying to spread that message to the world. What this meant practically was expansion: “‘My blood craves action,’ he wrote in 1943. ‘I desire advancement! My spirit calls for progress! Thank God for the glory of the past! But let’s do better tomorrow!’” (33) Roberts’s aspirations were not unlike early Christians, who went out to preach the gospel in all the world. But words like “advancement” and “progress” can become manipulated in someone’s mind when their beliefs give them a myopic view.

Advancement and progress required funding, so Roberts became an expert fundraiser. In his first ministry position, there was no house for the minister, so Roberts, his wife, and two children lived with another family in town in a two-bedroom, one-bathroom home. Feeling the pressure to move out of the town if he could not find a more suitable living situation, Roberts told the congregation that they should practice sacrificial giving: “the greater the sacrifice, the greater the blessing.” (36) Roberts called such giving “seed money” that God would use to produce an abundant harvest. People started giving immediately and he got the house.

It was after this initial foray into fundraising that Roberts found the guiding principle behind it. Opening his Bible one day, he saw a passage: “Beloved, I wish above all things that thou mayest prosper and be in health, even as they soul prospereth.” 3 John 2. After reading the passage, Roberts “was floored” and said the words “had gripping power.” (37) God not only wanted Roberts to be physically healthy—which he experienced in his healing—God also wanted him to be financially prosperous.

When someone is a true believer, they tend to interpret words or situations to align with their established beliefs. People are particularly susceptible to such thinking soon after they come to believe—in the euphoria of a newfound way of life, they see everything as either supporting or opposing that new life.

For Roberts, he did not have to wait long for what he thought was divine confirmation of his prosperity gospel. The same day that he read that passage, he asked his wife, “Do you believe God will give me a new Buick?” The family’s car had seen better days. After his wife expressed her incredulity that God would give Roberts a Buick, their neighbor, a “Mr. Gus, looked over the fence and asked Oral if he needed a new car.” (38) It turned out that Mr. Gus owned a Buick dealership and, even though Mr. Gus was not even a Christian, “he was impressed with the young preacher, who he believed was going to ‘do something unusual in the world.’ He wanted to help strengthen Roberts’s faith by giving him a new car.” (38)

The Buick was, for Roberts and his wife, a sign of divine favor that confirmed the prosperity gospel for them and accelerated their efforts to spread it. And the ministry grew quickly. Roberts started traveling and giving revivals, which quickly outgrew the churches or civic auditoriums they were held in. Roberts wanted to control the revival experience, so he bought a tent that fit 2,000 people. That was in 1948. He quickly upgraded to a 3,000-person tent the same year, and then, in 1952, was up to a 12,500-person tent, which was regularly filled with 15,000 people by the end of the 1950s.

Roberts became known for his healing ministry. “Oral believed that his message of divine healing tapped into something that Americans needed.” (48) He was worried about “the United States’ moral, physical, and spiritual decay” based on what he saw in post-war America. And in post-war America, TV arrived on the scene. Roberts’s show went on the air in 1954, and after some re-working of the format, launched again in 1955 to provide, in the words of one commentator, “a million front seats” to the revival experience.

The change in format also brought a change in fundraising. Roberts introduced his new conception, the “Blessing Pact.” “He promised to use their money to win souls and earnestly pray that the Lord would return their gift in its entirety ‘from a totally unexpected source.’ If God didn’t return their money, he would refund the ‘same amount immediately and no questions asked.’” (58) This early effort led to decades of funding for his ministry.

And the ministry grew to include Oral Roberts University, a medical center, and many other things. Yet the foundations started to crack as Roberts’s belief in the prosperity gospel ran head on with the reality of the times. For example, “Oral’s belief in the objective weights and measures of seed faith was meant to be positive. He reportedly had little patience for people whom he deemed overly negative. Being too pessimistic in his presence was a firable offense. At the same time, seed faith could often—and would increasingly—sound sinister and cynical. In the midst of the Great Stagflation of the 1970s, Oral refused to accept the economic downturn as an excuse for Christians to not prosper. The American economy might be susceptible to the ups and downs of the marketplace, but God’s prosperity was immune from the same ups and downs.” (132) When you are dependent on donations from others, you need to make them true believers as well.

Roberts’s belief made him a lot of money. He was certainly prospering. And even after moving the bulk of his earnings into a trust for his children, a journalist quipped that Roberts was “‘No longer a millionaire, he merely lives like one.’” (134)

Roberts used increasingly questionable, and increasingly cringeworthy, tactics to get donations to maintain his lifestyle and ministry. In early 1987, Roberts told his audience that he promised God that he would raise $8 million for a health center in a year. When he was eight months into the year, and still $4.5 million short, he asked the TV audience to donate: “Oral asked his supporters to extend his life. ‘Let me live beyond March,’ he said.” (184) Those supporters stepped up and closed the gap, but people took note. Some voiced their opposition to Roberts “putting a guilt trip like that on other people.” (184) Two years later, Roberts said he needed $11 million to continue his work so that creditors would not “‘start dismantling’ his ministry.” (189)

By the end, Roberts had focused too much on the prosperity and strayed far from the gospel. The advancement and progress he believed in was not enough to sustain him or his followers.His supporters eventually lost their faith in Roberts.

Those who blindly followed Roberts finally started to question him toward the end, which is what we should all do. “Trust, but verify” was originally a Russian proverb and was referenced extensively by Ronald Reagan in talking (ironically) about the Soviet Union. He wanted to test the bounds of what they said before agreeing to something.

That is the same process that many religious believers have been through for millennia. True believers are not afraid of testing the bounds of their belief. That is what John Henry Newman talked about in his spiritual autobiography. He was intent on questioning things because “Ten thousand difficulties do not make one doubt, as I understand the subject; difficulty and doubt are incommensurate.” Apologia pro vita sua, chapter 5.

True believers are important, and they have often shaped the course of history, for good or ill. On this Fourth of July, remember that the Founding Fathers were true believers as well. It took true believers to understand that “it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.” Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, Madison. It’s unlikely that they would have accomplished what they did without a firm belief in God, man, and the potential of a new republic.

Today, as we give thanks for the blessings of our country, let’s recapture the founding fathers’ vision that even with the many difficulties we experience, we can build a nation that promotes life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all. That should be something we can all believe in.

Remember to turn every page. Enjoy your holiday weekend. Please let me know whether you need anything.

Best,

Aaron

Page references for this book are from the Large Print edition. Pro tip—if you are getting books from the library, the Large Print versions are usually easier to get because they have fewer holds.