Turn Every Page: History of the Southwest, revisited

The forgotten characters who helped to shape the Southwest

Much of my recent reading has been focused on 19th Century American history related to a lumber magnate and philanthropist, Theodore Basselin. In reading about the United States between 1850-1900, many authors rightly focus on the Civil War and Reconstruction as the major events of the time. But when a major historical event or series of events defines a historical period, we sometimes forget that other people were doing other things in other places.1

For example, when the Franciscan missionary and priest Francisco Tomas Garcés was expelled from Hopi land in northern Arizona, “Garcés gave a short speech on peaceful co-existence and brotherhood before being forced to rapidly depart. Later he recorded the experiences in his journal and dated it at the bottom, July 4, 1776.” Trimble, Arizona: A Cavalcade of History, 68. While the American founders were meeting to discuss forming a new nation, Garcés “was helping to map and prepare for European habitation” a land that “would be part of the colonists’ new nation.” Jeremy Beer, Beyond the Devil’s Road: Francisco Garcés and the Spanish Encounter with the American Southwest, 9.

Centuries before these early Spanish missionaries and explorers stepped foot on what would become American soil, missionaries had left Europe to colonize and Christianize the new world. Augustine Thompson has a comprehensive study of Dominican brothers around the world, including stories of early missionaries in Mexico and the United States that make our lives seem pollyanna-ish.

One such story is of Marcos de Mena, a Spanish brother “born in Villar del Pedro near Talavera, Spain.” (Thompson, 142) Headed for Mexico in 1553, he was shipwrecked with others near the Mississippi River. “Almost immediately, the stranded party was attacked by Indians.” Id. Then, after Brother Marcos escaped, he and two companions caught up with the rest of their party. “After twenty exhausting days on foot, they reached a river, probably the Trinity River in what is today eastern Texas.” Id. And “[w]hile camped on the banks of the river, they were again attacked by Indians.” Id. This time he escaped, but he was found by the Indians later and “took seven arrows, one in the face, and fell to the ground.” (Thompson, 143) His brothers buried him in a shallow grave in the sand.

Miraculously, Brother Marcos survived. “Marcos dug himself out” of his grave. “He found himself bloody, naked, and riddled with arrows.” Id. “In an unbelievable trek, not even considering his physical condition, Brother Marcos made his way overland, some seven hundred miles, to the Pánuco River in central Mexico.” Id. After collapsing on the riverbank and being transported another twenty miles by compassionate Indians, Marcos was able to return to Mexico City where he “underwent painful surgery to remove the arrows. The whole adventure had taken between twelve and eighteen months.” Id.

Two centuries later, missionaries from Spain would start to explore more of the Western United States. The best known are likely the Franciscan Father Junipero Serra and the Jesuit Eusebio Kino (see Chapter 10 of Not Counting the Cost for more on Eusebio Kino). Beer describes Kino as “[t]he greatest Jesuit missionary to labor in this area” and “a captivating, attractive, erudite, thoroughly irrepressible, wavy-haired Tyrolean.” (Beer, 44) “No priest would be more committed to restless exploration, be more consumed by visions of expanding New Spain’s northern frontier, or have better relations with the region's natives until Francisco Garcés came along three-quarters of a century later.” Id.

Beer just published a few weeks ago a remarkable biography of Serra and Kino’s successor, Francisco Garcés. Beyond the Devil’s Road: Francisco Garcés and the Spanish Encounter with the American Southwest chronicles Garcés’s arrival in Mexico, his placement in modern-day Southern Arizona, and his many travels throughout the Southwest. Part missionary and part explorer, Garcés seems to move back and forth between those roles with alacrity. “Fray Francisco Thomás Garcés, a humble man, cut from the same cloth as the great Kino, was the priest assigned to the Arizona missions.” (Trimble, 66) “Like Kino, Garcés was the consummate missionary, always in search of souls to harvest. A year after his arrival, the gregarious friar had learned to speak the Pima language fluently. In 1771, he headed west in search of a land route to Alta, California, which would link up with the missions recently established there by the legendary Franciscan padre, Junipero Serra. Using three Indian guides and a horse, he followed Kino’s old trail, Camino del Diablo, to the Yuma villages on the Colorado. This expedition convinced Garcés that a land route was possible.” (Trimble, 66-67)

There’s much more to this story, and Beyond the Devil’s Road is a welcome addition to this body of research. Padre Kino is certainly worthy of attention. “Kino founded twenty-four missions. With the founding of Tumacácori and Geuvavi (1691) and San Xavier del Bac (1692), he also expanded the Spanish frontier northward into today’s Arizona.” (Beer, 46) “Kino made at least fifteen expeditions into Arizona, entering the territory on three occasions by way of the deadly Camino del Diablo.” Id.

Unlike Kino, Garcés is not known generally beyond those who read about the history of the Southwest in the 18th century. But he should be better known. “Garcés ‘had accomplished a feat which Kino had three times tried in vain.’ Indeed, it was a feat that no European on record had achieved.” (Beer, 134) This is a common theme with Garcés—he was an overachiever compared to other missionaries of his time. He brought a different approach to his missionary activities: “By the standards of his era Garcés was kind and patient. . . . Over time he would become kinder, more patient, more separated from his peers in these respects.” (Beer, 71) Beer describes Garcés’s actions as “patient, meet-them-where-they-are methods”—a useful trait for any missionary of any age. (Beer, 341)

Garcés was also a prolific explorer. “We know that he explored the lower Colorado River more thoroughly than had any European before him; that he successfully crossed the unforgiving sandy desert to the river's west and spied a route that would have taken him to San Diego, if only he had been given the opportunity; and that he sowed the seeds of a history-altering relationship with the Indian leader who greeted him on August 23, a man known among his own people as Olleyquotequiebe—‘The One Who Wheezes.’” (Beer, 127) Olleyquotquiebe was known to the Spanish as Salvador Palma.

Garcés worked to expand and explore the Spanish Territory and to minister to those he found there. “Despite the continuous raiding by Apache war parties, the tireless Garcés worked well among the natives. He sat cross-legged on the ground with them, ate their food and, although he was only thirty years old, earned the affectionate nickname ‘Old Man.’ Another priest described the humble friar aptly, saying, ‘God in his infinite wisdom must have created Garcés for the place in which he served.’” (Trimble, 66)

The place where Garcés served was even more unforgiving than it is today. A Jesuit missionary slightly before Garcés’s time “complained about the heat (it was so hot that ‘one cannot travel by day’), gnats, flies, scorpions, snakes, spiders, mice, rats, even ‘toads as big as a fully grown king’s hare,’ one of which startled him when it hopped onto the altar during Mass." (Beer, 66)

Garcés seems to have had a love for the land and its people that such difficulties did not deter him from his work. He had a desire to expand the scope and influence of the Spanish realm and the Church. As part of that work, Garcés traveled with the military commander Juan Bautista de Anza on two expeditions into modern-day California. “The first expedition left Tubac on January 8, 1774.” (Beer, 163)

This first expedition started eight months before another significant figure was born. Elizabeth Ann Seton was born in August of 1774 in New York. She was married, widowed, and founded the Sisters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Maryland in 1809. (For her story, I have to recommend Catherine O’Donnell’s wonderful Elizabeth Seton: American Saint.) A break-away group of the Sisters of Charity, based in Cincinnati, would be a source of great missionary activity in the Western United States.

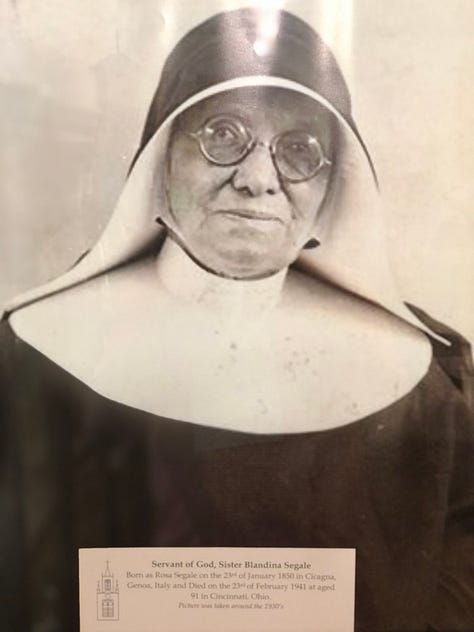

The most colorful example of these missionary women was Sister Blandina Segale. Sr. Blandina was a force to be reckoned with. Her memoir, At the End of the Santa Fe Trail, is a moving account of Sr. Blandina’s efforts to build institutions to care for the sick and needy. She moved from the east coast to Colorado at age 22—to Trinidad, Colorado, which was less exotic and exciting than the Caribbean Trinidad where she thought she was being assigned. Sr. Blandina worked hard in Colorado, where she established a school and met the infamous Billy the Kid. She likely saved his life, helping him recover from an attack and also convincing his enemies not to kill Billy. In one letter to another sister, Sr. Blandina refers to Billy the Kid as “my old acquaintance, ‘Billy the Kid.’” (Segale, 145) Yet it seems Billy had more admiration for Sister than as a mere acquaintance. So moved was he by her kindness toward him, Billy spared the life of some people in Trinidad at Sr. Blandina’s request: “We are all glad to see you, Sister, and I want to say, it would give me pleasure to be able to do you any favor.” Speaking to Sr. Blandina after she made her request, “I granted the favor before I knew what it was, and it stands. Not only that, Sister, but at any time my pals and I can serve you, you will find us ready.” (Segale, 75)

Billy and “his pals” served the sisters later, ensuring that Sr. Blandina and her sisters received safe passage on any train on which they traveled, such was his power to instill fear in others for any action against his friends. Writing to another sister, she said, “you will see how very little fear I have of Billy’s gang. Even if ‘Billy’ has mustered new pals, I’m marked for protection as well as anyone wearing my garb.” (Segale, 96)

Sr. Blandina left Colorado for Santa Fe on June 12, 1877: “The record is broken. We made the fastest trip ever known from Trinidad to Santa Fe.” (Segale, 99) There, she focused on building schools and hospitals that served as the foundation for the many social works the Catholic Church would perform in the area for centuries.

Garcés communicated with Franciscans in New Mexico a century earlier in 1774. He told them about the prospect of creating a route from Santa Fe to the Pacific coast at Monterey. This was always Garcés’s dream—to open a path from the Primería Alta to the established missions of the California coast.

For Garcés, these explorations were more than an attempt to reconnoiter areas previously unexplored by the Spanish. Garcés seems, from Beer’s exhaustive research, to have a genuine love for the land and its people. At some point, “[t]he momentousness of his journey had now fully dawned on Garcés. Rather than simply finding sites for new missions, he had discovered new routes, new peoples, new possibilities, new worlds.” (Beer, 136)

Garcés was beloved by many of the Indians to whom he ministered, and with whom he developed close bonds. But not everyone was happy about Garcés work, or the Spanish presence throughout the region. Francisco Palma, the asthmatic chief Garcés had met along the way, sent a group of warriors to peacefully bring Garcés back from the frontier. One rebel warrior, Francisco Xavier, did not like Garcés or the Spanish in general, and happened to be the first to find Garcés and his companion, Fr. Barreneche. Xavier believed that Garcés must die.

One of Xavier’s men entered the house where Garcés and Barreneche sat, drinking hot chocolate. “‘Stop drinking that,’ he demanded. ‘We’re going to kill you.’ ‘We’d like to finish our chocolate first,’ Garcés replied, finding within himself a vein of black humor. ‘Just leave it!’ was the warrior’s irritated response.” (Beer, 327) “As soon as [the priests] stepped outside, they were viciously clubbed to within an inch of their lives.” (Beer, 327-28) The priests died shortly after and are venerated as martyrs.

Garcés then seems to have been forgotten. “A succession of anticlerical regimes would to various degrees oppress, even terrorize, the Catholic Church in Mexico for many generations. Garcés and his fellow martyrs faded into obscurity.” (Beer, 334) Garcés was not rediscovered among historians until 1954—more than 170 years after his death.

And yet, with all of the good that Garcés did, historians that know of him often consider him a failure. The Indians to whom Garcés ministered were not converted in a way or to an extent that would have made historians consider it a victory. But as Beer points out in his Epilogue, the enduring faith among the tribes Garcés ministered to is a testament of his success, even if no one could have realized it at the time. Based on what he knew at the time, Garcés seemed to question his own level of success. As Trimble describes it, Garcés had said: “We have failed. It is not because we haven’t tried. It is because we have not understood.” (Trimble, 69)

Understanding is key to a missionary’s work. He must understand the people to whom he ministers. He must understand their language, their land, and their history. We, too, must seek to understand the world around us. For those who reside in the Southwest, these stories are part of our shared history. And they are worthy of study. If it is difficult to think of reading a historical work, Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop is a good, though fictional, description of life in the missions in the Southwest to get you started.

Knowing your history, and learning about these great historical figures, deepens your appreciation of where you are, and how the society we have today came to be. Just start reading.

Remember to turn every page. Enjoy your weekend. Please let me know whether you need anything.

Best,

Aaron

This is why I regularly recommend Jacques Barzun’s From Dawn to Decadence, which presents history in a way that allows you to link various historical events around the world and avoid the myopic view some historians have.